Listen to the latest episode of Credit Exchange with Lisa Lee

Published in London & New York

10 Queen Street Place, London

1345 Avenue of the Americas, New York

Creditflux is an

company

© Creditflux Ltd 2025. All rights reserved. Available by subscription only.

Opinion Credit

Huge lending from banks to private credit could cause systemic problems

by Duncan Sankey

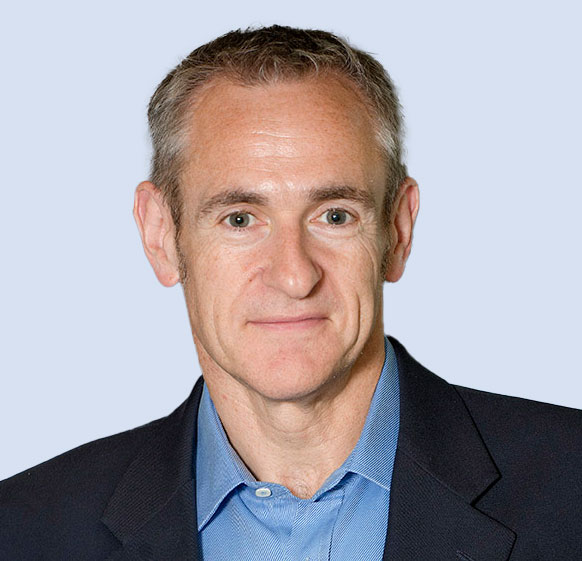

Duncan Sankey

Portfolio director and head of credit research

Cheyne Capital

There is little evidence of ‘cockroaches’ in credit. But in one sector, problems may just be hidden

There has been much talk of late of credit ‘cockroaches’. The metaphor presumably addresses the fact that cockroaches are rarely found alone and shun the light. However, when we shine the torch into the dark spaces we can reach, there isn’t much current evidence of an infestation.

There are a few isolated colonies but their provenance is well understood and they are containable. 60-day+ past dues in subprime auto loans have reached record levels, reflecting poorly underwritten 2021-22 vintages and soaring vehicle ownership costs. We have seen a mechanical spike in bad student loan debt following the resumption of collections/reporting. Finally, the Fed has flagged issues with regional bank CRE portfolios that may result in isolated needs for drastic action but, in general, should be mitigated by falling rates and contained by healthy capital levels.

US banks appear to be stable

More generally, the latest round of bank results showed no marked deterioration in asset quality. 20 or so money centre and regional banks surveyed by BofA showed a small average improvement in non-performing loans (NPLs) as a percentage of total loans both sequentially and year-on-year in Q3. True, the level was higher than that prevailing in 2019, but only marginally. Moreover, in 2019 the effective Fed Funds and 10-year Treasury rates were a full 1.5 and 2.2 points lower, respectively, than those prevailing currently; we should by rights expect NPLs to be materially higher now.

The same applies to credit cards. 30-day+ delinquencies on general-purpose credit cards are at close to post-millennium lows (they did dip slightly lower in the liquidity-soused aftermath of COVID) despite the prime rate (off which US cards are priced) being at its highest point since the run-up to the GFC. Even in buy-now-pay-later, where lending is usually skewed towards both sub-prime borrowers and younger cohorts who are among the most cash-strapped, the books look quite clean: at Klarna, realised losses as a percentage of GMV declined by 1bp y/y in Q3, while fair-financing 60-day+ delinquencies remained stable. 30-day+ delinquencies at Affirm (ex-Peloton) on recent vintages also show no unusual negative variances.

And what of publicly traded corporate bonds/loans? Global speculative-grade default rates are trending down and remain below long-term averages. While the inclusion of distressed exchanges and liability management exercises certainly pushes the number higher, neither the rate nor the trajectory gives immediate cause for concern, especially given US five-year refinancing needs that showed their first dip since 2018. Credit concerns do not usually trouble investment-grade (outside of fraud) and, in any case, this part of the market is broadly enjoying robust profitability, pre-COVID levels of leverage, rising credit quality (as measured by ratings) and ample liquidity.

Where the data doesn’t reach

The common factor to all these markets is transparency. We have plentiful data from multiple sources to illuminate problems as they develop and a wealth of historical data against which to gauge them. However, in the world of private credit, which has undergone exponential growth in the past few years, that may not be the case.

Intuitively, credit experience for this market should be no worse than that for broadly syndicated loans. However, we know from experience that when a surfeit of liquidity chases an asset class, it rarely augurs well for underwriting quality. True, much private credit is rated, but the proliferation of new rating agencies to which managers may turn raises questions about the quality of the ratings and the risk of ratings shopping.

An investor in a publicly traded HY deal can check Bloomberg for the ratings and can interrogate the agencies on discrepancies; not so their private-market peer. Even internal bank ratings may prove less than reliable if they are based on a probability of default history that does not reach back far enough to include the post-GFC recession. In the absence of comprehensive public disclosure, investors are required to place faith in the credit capabilities of the manager.

At the investor level, getting it wrong could prove expensive. Outside of ETFs, private credit does not enjoy the liquidity or pricing transparency that can be found in the public debt markets. The use of mark-to-model pricing could provide a false sense of security if credit stress is building in the underlying assets.

At the systemic level, the extension of over USD 1tn from banks to private credit and the exposure of retail to private credit through ETFs challenges the notion that major issues could be contained. It’s not the odd cockroach you see on the kitchen floor that is the problem; it’s what you can’t see swarming beneath the floorboards.